As I stare at the blank screen, preparing to write, I have more questions than answers.

I question what I can possibly say to you about racism, white supremacy, and police reform that will open you up, rather than shut you down. I question if I have already lost you, writing those three hot-button terms in the first sentence. As I write this at the end of 2016, so many of us are feeling raw and weary. I see this rawness as a space for growth and connection among hearts which have been broken open. We as a nation have entered a new phase in the fight to make real our country’s promise that all are created equal, endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights to Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.

There are three lessons that I learned this summer and what to share with you. The first lesson is about my perfectionism, a legacy of my conditioning in the culture of whiteness, which silences me by insisting that questions are a sign of weakness. The second is when I have questions about an issue, I need to listen to those the issue most gravely affects especially if they are angry. And, the third lesson is that anger is not at odds with love and nonviolence; in fact, to seek the truth in love. I must speak the truth in love. This means expressing my anger before it turns to violence — whether that be the implosive violence of bottling my emotions, or the explosive violence that comes when the bottle bursts.

All three of these lessons involve listening. So, I must listen more than I speak. On Facebook, I tended to share others’ words more than crafting my own. I let comments play out versus joining in the debate. This act of “online listening” is shaded in my white perfectionism. It’s the part of me that says I have to have all of the answers before I can engage in the conversation. The lesson here is; I do not need to have all the answers. Releasing this piece of my whiteness allows me to speak and act. Being a part of the race conversation is consciously rejecting the cultural myth of my European Enlightenment-era ancestors. I am a work in progress, and only as such may I be part of my society’s healing.

My second lesson is to listen intently to friends, acquaintances, and strangers of color. To hear their pain, rage, grief, trauma, despair, impatience, fear, and hope. I am listening closely to those who are willing to tell me how my “well-meaning-white-man” actions are hurting them, however unintentionally, because my intent does not negate the impact. The road to hell is indeed paved with good intentions, and my defensiveness only serves to steamroll the asphalt.

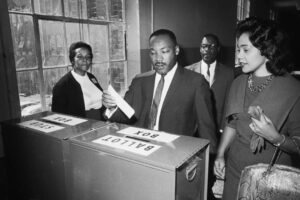

My greatest challenge is listening to mass media, political rhetoric, religious leaders. It is hard to hear those in power construct their narratives around bloody summer of 2016. More myths have been handed down by my European Enlightenment-era ancestors. Some sound like the police chiefs in Selma and Montgomery in the 1960s. Others sound like the moderate clergy Martin Luther King critiqued in his Letter from a Birmingham Jail. Most maddening are those who invoke King’s words, taking them out of context to shame and silence Black pain and anger, when King himself promoted militant nonviolence. As I listen, I struggle to honor my promise to seek and speak the truth in love. It is so easy to succumb to hate, because it distances me from those with whom I disagree. Love insists I meet them in our common humanity, however messy and tender it may be.

For inspiration to meet in Love, I’ve been listening to leaders in the movement for Black lives who lead with their hearts open and bleeding: leaders of color, who speak truth to power structures without scapegoating the people in them; white co-conspirators who insist that white supremacy can no longer have their people, and call white working-class people in to the movement for collective liberation. From them, I hear a different narrative than that of the whitewashed powers mentioned above. Their stories are more complex and not so neatly packaged. I have come to trust messy stories because truth rarely comes wrapped with a bow; it has too many layers and threads to fit in a box.

Black Lives Matter is a movement for the full value of all lives—a value that remains unreached because Black lives remain at the gravest risk—followed by brown lives, trans and queer lives, and poor lives of all stripes. Acknowledging this reality does not devalue or minimize the real problems of non-Black bodies; it prioritizes the most urgent need, which in turn frees up energy to address all needs. I believe this is what Jesus meant when he said that what we do to the least of these (i.e., the neediest), we do to God (i.e., the totality of reality).

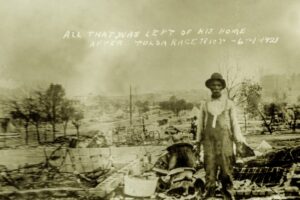

Working-class white people often struggle with this, and for good reason. We, too, have inherited a bum deal from the system of white supremacy, which is as much about economics as race. The economic factor is so obvious that many people categorized as White, especially those who are poor or working-class, are quick to say that the main problem in our country is class, not race. The big wrench in this argument is the invention and perpetuation of a racial caste system is what solidified the economic class system. Few people learn this piece of American history. So, white people need a starting point for anti-racism and for empathy with the struggle for Black lives which has culminated in the #BlackLivesMatter movement.

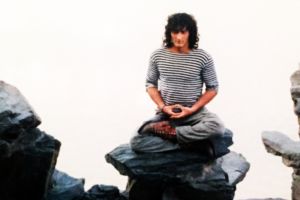

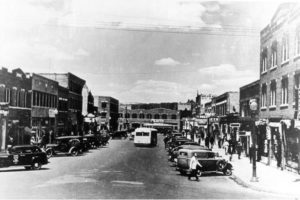

How did this 30-something, white, student minister come to these three lessons? Let me share my story with you. Though I don’t know what it’s like to be a person of color, I do know what it’s like to live in fear of the police. At nineteen, I was a queer, trans, anarchist punk in New Orleans. I survived capitalism by waiting tables, tending bar, and chemically altering my mind along with other poor white kids who congregated around Jackson Square at night. We were a hodgepodge of subcultures—punks, goths, anarchists, ravers, runaways, train-hoppers, potheads, queers—but we were collectively and not-so-affectionately known as “Quarter Rats” by the local gentry. The police were there to serve and protect “them” from “us,” even though realistically, we weren’t a danger to anyone but ourselves.

No one wants a trip to jail, and for a trans person, a trip to jail might mean a trip to the hospital or morgue. Fortunately, I managed to escape arrest but I knew of the horror stories from my fellow gender nonconformists. For this and many other reasons, we—the Quarter Rats and the queers—didn’t trust the police. They selectively enforced laws against us while turning a blind eye to the drunk, obnoxious tourists. They sought us out. They followed us. They kicked us out and ran us off. The society they served and protected had no place for us, so we made our own place on the margins of it—and we weren’t welcome there either.

I understand cycles of poverty, marginalization, addiction, and ill health. I find it significant that we were an almost exclusive white group. What was missing from our analysis was race. It was the one privilege we had, and thus we were blind to its impact.

If you had asked any of us if we were racists, we’d have laughed in your face. Still, we didn’t hang out with any Black kids in a city that was almost two-thirds African-American. We’d be the first to tell you not to go to past North Rampart street because it was “dangerous.” We were scared of poor Black people, even though we had more in common with them than we did with the middle-and-upper-class white people who lived in the Quarter. White supremacy convinces people who are categorized as white that they are inherently different from those who are categorized as non-white—dividing and conquering the many for the flourishing of the few.

This is not to say that there is no difference between people who are in different racial categories. But, there is a key difference between my experience as a trans, punk kid and the experience of millions of people of color. To ignore it misses the crux of the system of oppression. I can take off my flak jacket, dye my hair a natural color, put on a clean polo and khakis, and get a tip of the hat from a passing cop—whether I obeyed the law or not. I can hide my differences and my skin would protect me. People of color can’t hide their differences because they can’t take off thier skin. It doesn’t matter what they wear. It doesn’t matter if they, like Philando Castile, are college-educated with a successful career and no criminal record. It doesn’t matter if they have a four-year-old in the backseat. People of color can follow all the rules, right up to telling the officer that they have a legal, concealed carry firearm and they’re going to reach for your wallet—and they can still get shot for just for being there and being Black.

Philando and I had a few things in common. We were the same age. We had bachelor’s degrees from state schools. We’d studied and/or worked in education. We have loved and nurtured the youth in our lives. We were father figures to our partners’ children.

But, he did nothing wrong and he is gone. His family is without a son, a partner, a father. And I hung out with the wrong people in the wrong places at the wrong time and never got more than an empty threats from the police. I got a chance to turn my life around and Philando never went down that road in the first place. Some of this is chance, but much of this is race.

This is why I unequivocally stand with the value that Black Lives Matter to me. I am no longer willing to sacrifice my humanity to a white supremacist system. I am writing these imperfect words, and will keep writing, speaking, connecting, listening, and will never allow my broken-open heart to shut off to others’ humanity—no matter how much it hurts.

-

King, Martin Luther Jr. “Letter from the Birmingham jail.” In Why We Can’t Wait, ed. Martin Luther King, Jr., 77-100, 1963.

5 Comments

[…] Steven is the Pastoral Care Chaplain at All Souls and continues to fight for justice and against white supremacy. After the police killings of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, Steven shared why he unequivocally stands with the value that Black Lives Matter and is no longer willing to sacrifice his humanity to a white supremacist system. Read his story, The Humanity of Difference. […]

[…] more on beyondbelief.online about learning new perspectives and finding our commonality among our […]

[…] Steven L. Williams serves as the Pastoral Care Chaplain of All Souls Unitarian Church in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Steven is a regular contributor to BeyondBelief.online and is the author of our feature story, The Humanity of Difference. […]

[…] Steven is a regular contributor to BeyondBelief.online and is the author of our feature stories, The Humanity of Difference and Brokenness: There is more to the […]

[…] Steven is a regular contributor to BeyondBelief.online and is the author of our feature story, The Humanity of Difference.Cover Photo: mindandi – […]