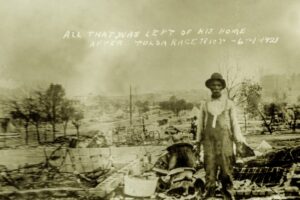

In the last two articles of this series, I have discussed some myths around the Tulsa Race Massacre. For a moment, I’d like to go even further back in our history to look at another event: the Boston Massacre, which occurred on March 5, 1770. Crispus Attucks was an escaped slave and made his living in the whaling industry. As Shomari Wills explains in his book, Black Fortunes, the shipping and whaling trades worked by an entirely different business model than plantation slavery. If you were a crew member on a whaling ship, you owned a share of whatever that ship brought back to port and sold, as written in the ship’s charter. Black men working on whaling ships and providing other services to the shipping industry (Attucks’ side-hustle was making ropes) could rise to a certain amount of notoriety and affluence.

Unfortunately for Attucks, he was in the wrong place at the wrong time when he and a group of fellow ropemakers got into a fight with British soldiers—who were responsible for policing the city of Boston and also worked to put pressure on the shipping trade and actively suppressing opportunities for workers. He became the first casualty in what was to become the Revolutionary War. So we can say that in one sense, that the first victim in the birth of our new nation was a free Black man asserting his rights, who was shot by police officers. It won’t be unfamiliar for you to learn that the eight soldiers who shot Attucks and four other men in the Boston Massacre were acquitted of the charges against them. Their defense attorney was none other than John Adams. Police excessive use of force with no accountability was etched into the nation’s DNA before it became a nation.

Before the Police were Funded

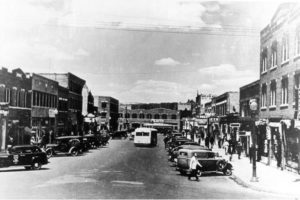

Fast-forward about eighty years, most large cities in the U.S. did not have a formally-established police force. Like volunteer fire brigades, police officers in the latter half of the 19th Century were a loosely-organized group of freelance, “constables.” The reason? Citizens did not want their tax money to pay for a standing military force in their cities. This logic will ring familiar to those who today are joining the movement to defund the police. New York’s rival fire brigades (depicted in the Scorsese film, Gangs of New York) and bungling police force were far from perfect. Still, the early history of these institutions could inform the current movement that we once lived in a country that did not have militarized police forces in all cities and that this discussion is by no means a new one.

Some of Those that Work Forces

These freelance police forces were often employed as slave patrols, tasked with capturing and punishing runaway slaves. After the Civil War, these former vigilante groups organized to resurrect the Klu Klux Klan. The Klan’s popularity soared in the late 1910s and early 1920s after former Confederate states established their new constitutions. During this period, the number one factor in whether an event such as lynching or the massacre of a town would occur was police enforcement. In some cases, police looked the other way when someone was lynched. In other cases, the police would willingly turn over an arrested Black man to be lynched by a mob. Some officers attended or were participants in lynchings.

This reign of terror against Black communities did not go unanswered. In Tulsa, J.B. Stradford and A.J. Smitherman actively worked throughout Oklahoma to stop lynchings. The two also worked to bring W.E.B. Dubois to Tulsa to speak about structural racism—a common theme in Dubois’ newspaper The Crisis, and his book Darkwater. Southern White Democrats were enraged at the idea that these men of prestige and power would dare advocate for equality. Before the 1921 Tulsa Massacre, articles in the Tulsa Tribune criticized DuBois and his followers, published sensational articles about Greenwood lacking law and order. After the massacre, Black Tulsa was blamed for inciting race tensions that led to Greenwood’s destruction.

The Battle for Civil Rights

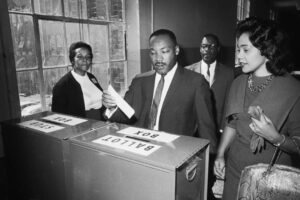

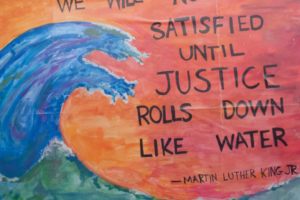

One finds that Tulsa’s story is also America’s story. Institutionalized racism in Minneapolis reaches as far back as the Civil War and Reconstruction eras, is formalized as part of the law in housing discrimination, voter disenfranchisement, and militarized policing. Civil rights battles such as the 1964 Harlem Riots, the 1967 Northside riots in Minneapolis, and similar police violence against Black communities again prompted activists to speak out and demand justice. Again, like during the race massacres of the late 1910s and early 1920s, Black people were blamed for riots and inciting race violence. Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. responded in a speech in April of 1967 at Stanford University:

“I think America must see that riots do not develop out of thin air. Certain conditions continue to exist in our society which must be condemned as vigorously as we condemn riots. But in the final analysis, a riot is the language of the unheard. And what is it that America has failed to hear? It has failed to hear that the plight of the Negro poor has worsened over the last few years. It has failed to hear that the promises of freedom and justice have not been met. And it has failed to hear that large segments of white society are more concerned about tranquility and the status quo than about justice, equality, and humanity. And so in a real sense our nation’s summers of riots are caused by our nation’s winters of delay. And as long as America postpones justice, we stand in the position of having these recurrences of violence and riots over and over again. Social justice and progress are the absolute guarantors of riot prevention.”

Police Trained to be a Military Force

In March 1991, Rodney King was stopped at the intersection of Foothill Boulevard and Osborne Street in Lake View Terrace in Los Angeles for speeding. Four police officers tased King multiple times, kicked him repeatedly, and struck him with metal batons 57 times. The officers were acquitted of all charges against them, with a jury agreeing with the defense that the officers were only following their training. Nearly all of them had a record of using excessive force. Sergeant Stacey Cornell Koon received three reprimands during his career. Officer Theodore Briseno had been previously suspended from the force for using excessive force. Officer Laurence Michael Powell was described as an “overaggressive and slightly sadistic police officer of questionable judgment.” In one incident, Powell struck a handcuffed prisoner. In another, he cursed at a Black motorist for driving in a white neighborhood. In a third incident, the LAPD settled an excessive use of force claim to the tune of $70,000. During the 1980s and 1990s, the LAPD was hailed as the best police force in the nation, despite a shocking record of racism and excessive use of force.

This wasn’t an isolated incident in Los Angeles or the rest of the country. Frank Hernandez, the LAPD officer who was filmed brutalizing and spitting on Richard Castillo this past April is connected to three previous shootings, one of which involved him shooting a teenaged bystander in the leg, then falsely accusing the kid of having a gun to cover up his malfeasance. Brett Hankison, one of the detectives who murdered Breonna Taylor in bed while executing a search warrant at the wrong address, had faced previous accusations—ranging from raping women in exchange for not arresting them to allegations of excessive force to lawsuits for illegally planting evidence. Derek Chauvin, one of the officers who asphyxiated George Floyd while he begged for his life, was involved in three shootings, and at least 12 misconduct complaints, none of which resulted in disciplinary action. Tou Thao, the officer who enabled Chauvin, was previously fired and sued for excessive force.

None of This is New

As in post-WWI Tulsa, activists have mobilized to protest and call for policy changes to increase police accountability and reduce excessive use of force. And now, as then, the police are fighting back. In Minneapolis, protestors and police officers are still clashing. In Louisville, police shot seven demonstrators that were seeking justice for Breona Taylor in late May. In Greenwood in 1921, an unidentified force in white shirts and khakis worked to burn and loot the neighborhood. Today an unidentified force in tan military uniforms is disappearing protestors in Portland.

These battles aren’t new; they’re just now being seen by a larger audience. To Native, Black, Latino, and other minority communities (let’s not forget that the fight for LGBTQ rights was also a violent movement—marked by events such as the Stonewall riots in New York and the assassination of Harvey Milk in San Francisco), none of the widespread clashes between protestors and police is new. We have heard police use racial slurs against us all our lives. We know that the police revel in brutality. The only difference is that today America is seeing these events in real-time, on our cell phones.

We Must Face our Demons

The problem is structural—not an issue of training and not an issue of interpersonal feelings. There is reliable data that suggests that police misconduct overwhelmingly stems from clusters of the same officers who repeatedly offend and are not disciplined (much like the spread of a virus). In April of 2019, Minneapolis mayor Jacob Frey tried to ban “warrior” style police training. The police union President Kroll called the ban “illegal” and offered free warrior training for all interested officers. This is the same training that Tulsa police Major Travis Yeates teaches. Yeats also includes lessons about how to defend these uses of force. He was recently quoted on radio station KFAQ for saying that the department shoots fewer of Tulsa’s Black citizens, “than we ought to.” While Yeats was reprimanded in the media by Tulsa’s mayor and police chief, he has yet to receive any disciplinary action for his comments.

Last month, on the eve of President Donald Trump’s Juneteenth weekend visit to Tulsa, Mayor G.T. Bynum commented on CBS Sunday Morning that race was not a factor in the murder of Terrance Crutcher. From the city police participation in the 1921 massacre to the removal of Drew Diamond as police chief in 1991 to Tulsa’s current methods of police training and continued resistance to enact any formal structure of accountability, all the evidence points to the contrary. We cannot hope to heal as a city until we acknowledge our history and understand its connections to the policies that are in place today.

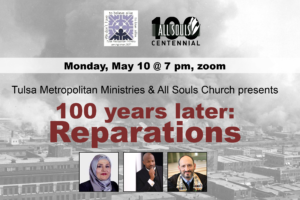

Carlos Moreno is a member of All Souls and our Criminal Justice Outreach team. He recently launched the site, The Victory of Greenwood, telling the stories of Greenwood from perspectives of the heroes and entrepreneurs who built Greenwood, and rebuilt the community after its destruction. Carlos is an advocate for criminal justice reform in Oklahoma. Read more from him about CJO’s work in Poetic Justice and Prison and The Biology of Toxic Stress on beyondbelief.online.

The All Souls Criminal Justice Outreach team CJO seeks to care for those impacted by incarceration, to educate the community about criminal justice issues, and cultivate equitable reforms in Oklahoma’s Criminal Justice System. Please reach out via email or join our Facebook group if you’d like to join CJO or have questions.

1 Comments

[…] I discussed in my last article, we have a nation steeped in nothing less than the state-sanctioned killing of its own citizens. […]