Fed a steady diet of lies for years, incited by racist rhetoric, and given support by some members of the police and national guard, a white mob attacked. This attack occurred at the U.S. Capitol on January 6th, 2021. A century ago, these types of violent attacks swept across the nation. Today we know the stories of a few of the more heinous events: The Wilmington Insurrection. The Rosewood Massacre. The Elaine Massacre. The 1919 Chicago Riots. The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. It used to be hard to understand how people could so easily believe lies that supported their racist beliefs. Harder still to accept that these beliefs would drive people to violence and death—until we saw it happen in real-time on our screens.

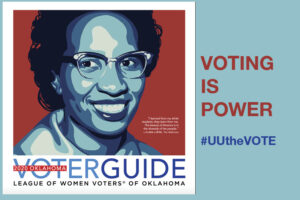

The Wilmington Insurrection of 1898 occurred as a result of white Democrats in North Carolina objecting to the results of the election in Wilmington, a city with a large population of Black voters. Over the next two years, North Carolina passed “grandfather clause” laws, effectively silencing the Black vote in the state until the passage of the Voting Rights Act nearly a century later (Oklahoma’s grandfather clause legislation was passed in 1910). There were several lynchings in southern states during and after Reconstruction, but in 1919, the country was so fearful of the rise of the level of education, political power, and wealth owned by Black communities that a wave of race massacres swept the nation. So many that the season was referred to by the NAACP as the Red Summer. It is only in the past few years that places like Wilmington and Chicago are uncovering the history of these events again and examining them with a new perspective, a new understanding that these were violent terrorists acts with political motives.

Tulsa’s Broken Promise

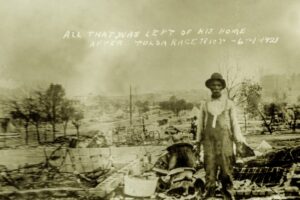

The Tulsa Race Massacre had a slightly different motive: Tate Brady and his business associates had planned to steal land from business and homeowners, forcing the Black community to move further north to the Turley area so that they could build a new industrial zone and train depot in Greenwood’s place. The destruction of 40-blocks of residential and commercial buildings, the killing of an estimated 300 people, the aerial bombing, the placement of thousands in concentration camps, the displacement of 10,000 people from their homes, the denial of fire insurance claims, the ordinances to prevent Greenwood from rebuilding—these events were not motivated by jealousy or sparked by a man stepping on a woman’s foot. Let’s get real. Let’s look at the facts. Let’s look at these events honestly and shed the myths we keep telling ourselves. Let’s stop pretending that this violence sprung from nothing.

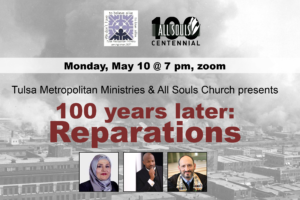

More importantly, let’s remember that reparations isn’t just a current conversation. A June 5th, 1921 article in the Columbus Dispatch described that former Tulsa mayor L.J. Martin was named chairman of a committee considering reparations for the damage done to homes since the insurance companies were “disclaiming responsibility.” The former mayor was quoted as saying, “Most of this damage was done by white criminals who should have been shot and killed. As the final outcome, we must rebuild these houses, see that the negroes get their insurance, and get their claims against the city and county.” The committee, established by the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce board of directors, suggested that the fund be set at $500,000 to pay for the property losses (roughly $6.6M in today’s dollars).

Mayor T.D. Evans placed the blame for the destruction squarely on the Black residents of Greenwood. Later that month, L.J. Martin’s committee was pressured to announce that no help, “financial or otherwise, be accepted to reconstruct the Negro district.” In a June 14th message to the Commission, Mayor Evans said, “Let the Negro settlement be placed farther to the north and east.”

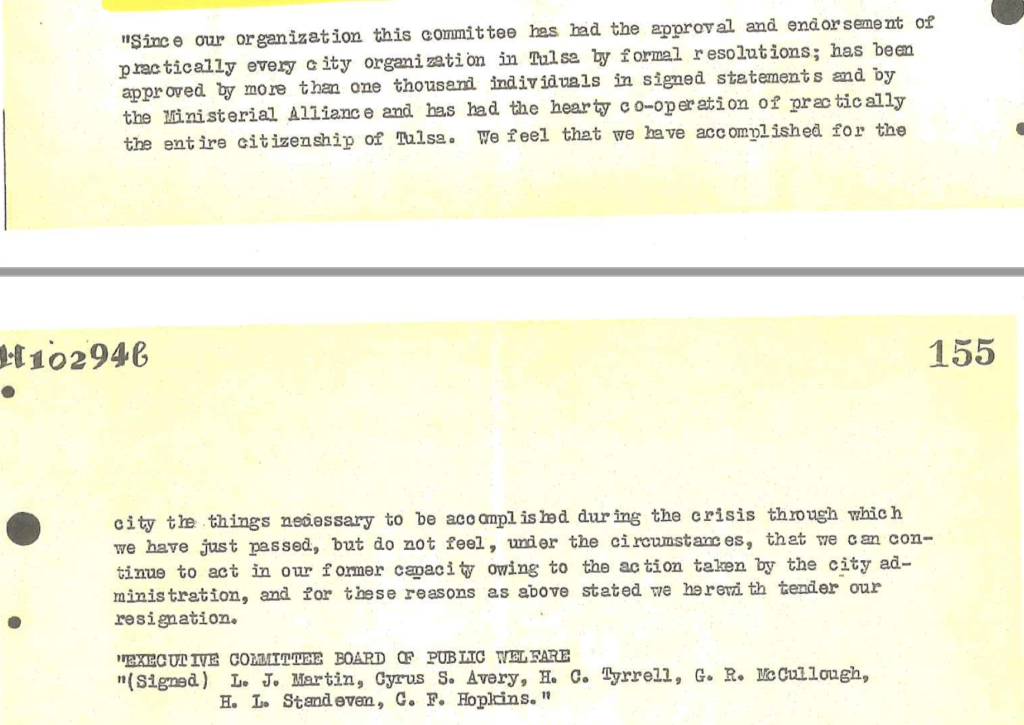

Under political pressure by the Mayor and City Commission, Martin’s committee was forced to tender their resignations on June 15th, and a new committee, the Reconstruction Committee, was established by the City Commission. Mayor Evans supported an ordinance to re-zone Greenwood such that any new construction had to be at least two-stories high and be made of concrete, brick, or steel. The Commission and the Mayor’s office collaborated to pressure residents to sell their land so that reconstruction would result in making Greenwood an industrial district to serve the Frisco rail line—a plan spearheaded in part by Tate Brady. In the months that followed, while O.W. Gurley, B.C. Franklin, and others fought for Greenwood’s residents to keep what little they had left, any talk of reparations was silenced.

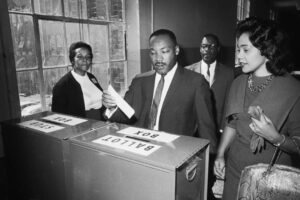

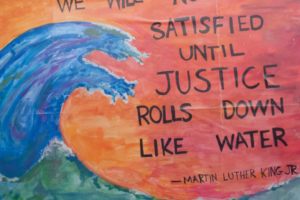

In 1921, Tulsa made a promise: To compensate those who lost their homes and businesses as a result of Greenwood’s destruction. In Dr. Martin Luther King’s famous 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech, he began with an analogy that I think fits our current conversation about reparations. He said that America made a promise. Its founding documents declare that all men are created equal. In the Emancipation Proclamation, the Federal government stated that it would, “recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.” The 14th Amendment to the Constitution, adopted in 1868, stated that, “No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” Dr. King observed that while the country had made these promises, it had yet to deliver on them. America, he said, had written a check that could not be cashed: “It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned.”

At a time when all eyes of the world are on Tulsa this year (yes; the history of Greenwood is known globally, not just in the U.S.), at a time when the Massacre has been featured in every major news outlet in the country and is the subject of two fictional HBO shows and several upcoming films and documentaries, at a time when the Human Rights Watch has made a case for reparations, we still don’t want to talk about what Greenwood really needs: Not another monument. Not another plaque. Reparations. Now.

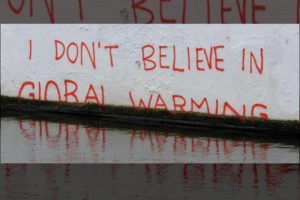

Viruses: Biological and Political

The nation’s abysmal response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the death toll that has resulted is directly connected to the nation’s public policies, which uplift wealthy white communities. Black, Indigenous, and people of color are the ones who do the heavy lifting to keep those systems intact, and they are the ones who suffer most when those systems break down. This is a phenomenon that the medical community has discussed. While people of color are more likely to contract the virus, they’re also the same groups of people who are asked to work the hardest without any options to self-quarantine or take time off work for their health. People of color make up the majority of essential workers in food and agriculture (50%) and in industrial, commercial, residential facilities and services (53%). We have both a health crisis and a crisis of racist public policies.

Despite the overwhelming evidence that BIPOC communities are suffering the most, these very communities are fighting the hardest for workers’ rights for all, voting rights for all, higher wages for all, healthcare for all, and economic justice for all. And what we saw on January 6th, 2021, was the white backlash against that. If there’s anything to be learned from these simultaneous crises, it’s that civility, prosperity, and democracy is a process. We can’t take it for granted (we should never have, but we know that now more than ever). It’s work. It ebbs and flows. It can be damaged easily, and that damage can last for generations. But there’s also hard work and hope, and love. In Tulsa, Greenwood rose every time it was beaten down because its people worked hard, loved, and never lost hope, no matter how bad things got in 1921, 1971, 1991, or 2020. Greenwood’s leaders have always been Tulsa’s leaders—pushing toward progress, pushing toward unity, pushing toward justice, pushing toward what we all want our city and our nation to become. Always demanding that Tulsa cash its check.

At times, it can be very uncomfortable, even overwhelming and depressing to look at our racist history. However, acknowledging that America’s progress has come at the cost of Black, Latino, Native, and Asian-American lives and opportunity is necessary. It moves us from viewing events like the attack on the U.S. Capitol and saying simply, “this is not America.” That statement removes us from the personal responsibility we all have to actively work to heal the nation. It lets us quickly put events like this in the past, in a box, so that we can ignore them. As historian Nikole Hannah-Jones explains, “in a country that has been multi-racial since 1619, this is exactly who we are.” When we turn away, we can justify not feeling like reparations need to be made. Race Massacre survivor George Monroe said in a 1999 interview with KOTV, “It’ isn’t the money. It’s just the idea. [Not receiving reparations] let me feel like [the Massacre] never happened.” How many in Greenwood have been made to feel that way, by their city, for 100 years?

Where do we go from here?

In 1967, after the passing of the Civil Rights Act and Voting Right Act, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. traveled to Jamaica for a year of self-seclusion to reflect on the movement and what steps were needed to continue its progress. The year of reflection resulted in King writing his fourth and final book, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? In it, he made clear that the Civil Rights Movement was far from over. He pointed out that moderate American whites have inaccurate, unrealistic views about what it was like to be Black in the United States. He asserted that all Americans must unite to fight poverty and create new national policies providing equality of opportunity.

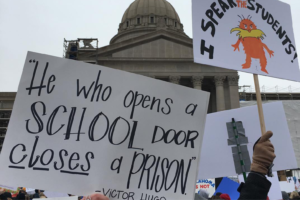

Quoting heavily from economist Henry George’s 1879 book, Progress and Poverty, King pointed out that the building of communities increases land value (and thus improves cities and states overall). Yet, he pointed out, Black and other minority communities in 1967 were left to languish with poor schools, few job opportunities, and crushing poverty. Think of the ways in which Greenwood in 1921 and in 1971 was not allowed to continue building their community. King also advocated strongly for the elimination of systemic poverty, writing, “I am now convinced that the simplest approach will prove to be the most effective—the solution to poverty is to abolish it directly by a now widely discussed measure: the guaranteed income.”

Ideas being discussed by progressives, including eliminating student debt, raising the minimum wage, establishing a universal basic income, and defunding the police, to some people, seem very radical. How can we afford them? How would we implement these systems so that people aren’t taking more than their fair share? How are these systems fair to people who have worked hard for generations to establish their wealth? Is giving to one group of people taking from another?

Two Models for Change

As you’ve read above, these questions have been debated since the 1870s. White people, intolerant that others should be in positions of power, have fought wars in cities to stay in control. This is the story of America since before its founding. While we’re drowning, instead of finding ways to stop drowning, we’re stuck discussing the water. It’s time to stop debating the source of these problems (we already know what they are) and start talking about solutions before it’s too late.

A few emerging public policy theories build on past work on eliminating systemic racism and creating a more equitable nation. One is the Abolitionist Model. The model gets its name from criminal justice advocacy to abolish the death penalty, abolish pre-trial detention & bail, abolish ICE, and defund the police. However, speakers and writers adopting this model are speaking more broadly now, defining its goal now as, “building a world where we work together to meet one another’s needs; a world built on communities of care and networks of nurture; a world in which every living being has access to safety, self-determination, freedom and dignity.” If such a world is radical, I say let’s get radical and do everything we can to build it.

Another quite interesting model I have heard from Tulsa’s own local historian Hannibal Johnson. In a TEDx talk given for Tulsa Community College last year, Johnson outlined three pillars of racial reconciliation: Acknowledgement, Apology, and Atonement. I find this model intriguing because we can apply it in our personal lives, as well as in communities, cities, states, and nationwide. It is also not idealistic or esoteric. There is action at every step in Johnson’s process. He describes Greenwood as, “a community in search of unity.” In a recent article for the Tulsa Star, Kolby Webster agrees, writing that, “It is unfortunate that there appears to be such a disconnect between the community and the institutions meant to bring them prosperity…” I would argue that Greenwood is doing its part. The question in my mind is: Will the rest of Tulsa join Greenwood in its search for unity?

Taking the First Step

In the summer of 2019, a team of researchers, creative professionals, and I approached Reverend Marlin Lavanhar to produce a series of articles and book, titled The Victory of Greenwood. We had no desire to tell the same old tired (and inaccurate) myths of Greenwood. We wanted to uncover the truth, and we wanted to tell Greenwood’s full story—from its founding, to the Massacre, to Greenwood’s rebuilding, its second destruction during Tulsa Model Cities, and the relevance of Greenwood’s story to today’s deep-seated national racial struggles. What started as a small project to publish a book has grown into a research effort spanning almost two years. We’re also in the planning and fundraising stages of a series of events, a podcast, a video series, and an interactive map and timeline, which will be developed in partnership with the national nonprofit Code for America.

We have at our fingertips that first step in Hannibal Johnson’s model for reconciliation: Acknowledgement. We can learn more about Greenwood’s history and find in it a sense of connection and compassion. Our hope is that those in power will begin to see Greenwood in a new light. Greenwood’s history is vibrant, multifaceted, and fascinating. By learning the individual human experiences of Greenwood residents, Tulsa can begin to come together as a community promoting growth, cooperation, equity, and respect for all its citizens. Our goal for this project is for people to connect with Greenwood on a human level—not out of a sense of guilt, shame, or obligation. I want other people’s hearts to connect to Greenwood the way mine did. That transcends the Massacre, the centennial, local politics, and individual agendas. Let’s leave all that behind and connect the way Greenwood wants to connect: Finding unity. This is precisely the beginning of nonviolent action that Dr. King preached: Compassion begets justice.

We’re still waiting, but the day will come, no matter how long it takes, no matter how much work has to be done. As long as people are willing to do the work, and keep pushing. More than anything else, The Victory of Greenwood project is about the people who kept pushing toward that one day we all know is possible.

Carlos Moreno is a member of All Souls and our Criminal Justice Outreach team. He recently launched the site, The Victory of Greenwood, telling the stories of Greenwood from perspectives of the heroes and entrepreneurs who built Greenwood, and rebuilt the community after its destruction. Carlos is an advocate for criminal justice reform, an author, and Tulsa Race Massacre historian. Read more from him in Tulsa’s Greater Sin, Poetic Justice and Prison and The Biology of Toxic Stress on beyondbelief.online.