In August 2016, a photo of a five-year old Syrian boy, covered with dust and blood and sitting alone in the back of an ambulance after his family’s home was hit by an air strike, shocked the world and served as a brutal reminder of the devastating five-year civil war in Syria that has forced more than 10 million Syrians to flee their homes and left more than 400,000 dead.[1] The photograph prompted international outcry for an end to the deadly bombardment of the besieged city of Aleppo.

In the span of twenty-four hours, two starkly different images of refugees had emerged, one invoking compassionate outrage, the other invoking fear and suspicion.

The day after the photo appeared President Barack Obama mentioned the boy in the photo in a speech to world leaders at a refugee summit, calling for a greater commitment from governments, relief agencies, faith organizations, and businesses to provide assistance to and welcome refugees from around the world—mostly women and children— fleeing war and terrorism.[2] The same day, Donald Trump aired the first general election ad of his presidential campaign.[3] The ad focused on immigration, the central issue of Trump’s campaign, and threatened ominously that, if Hillary Clinton were elected, the United States would be flooded with tens of thousands of Syrian refugees and dangerous immigrants committing crimes and collecting public benefits would be permitted to stay. The ad went on to promise that Donald Trump would keep America safe by keeping terrorists and dangerous criminals out. With 65 million people displaced around the world, including 11 million Syrians, now, more than at any other point in history, a better understanding of who these refugees are and what they need is critical to moving toward a solution.

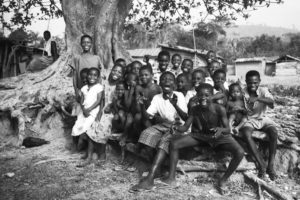

Unlike other migrants, a refugee is a person who has been forced to flee their home country because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.

Refugees leave their homes to escape war, violent political upheaval, or other life-threatening danger. More than half of the world’s refugees come from three countries: Syria, Afghanistan, and Somalia.[4] One half of the world’s refugees are children. Less than one percent of refugees will ever be resettled. [5] Some will eventually be voluntarily repatriated. Many more will remain for years or even decades in protracted refugee situations in host countries in the developing world, unable to fully integrate and with few means to educate themselves or their children. Turkey, Pakistan, and Lebanon host more than half of the world’s refugee population, though in most cases they are unable to accept refugees permanently.

The United States has a long history of providing protection to refugees fleeing persecution around the world.

In the aftermath of World War II, hundreds of thousands of displaced Europeans were resettled in the United States. Since Congress passed the Refugee Act of 1980, establishing the refugee resettlement program and the standards for admitting refugees to the United States, about 3 million refugees have been admitted to the United States. The number of refugees admitted each year has varied widely, from a high of 207,000 in 1980 to a low of 27,110 in 2002. Each year, the President sets an annual cap on the number of refugees that will be admitted, and determines how many refugees from each region of the world will be included in that number.

The allocations of refugee admissions respond to specific humanitarian concerns arising from war, conflict, and persecution around the world. During most of the years of the Obama administration, the annual cap on refugees ranged between 70,000 and 80,000. In late 2015, in response to record numbers of people forced to flee violence in their homes around the world, the Obama administration proposed a significant increase in the annual refugee cap—from 70,000 in 2015 to 85,000 in 2016 and 110,000 in 2017. Obama also called for the admission of at least 10,000 Syrian refugees. Still, even with these increases, only a tiny fraction of the world’s refugees will have the chance to resettle in the United States.

Refugees and the issue of refugee resettlement have largely been immune from the political controversy that has plagued the immigration debate in the United States for decades.

In fact, the resettlement program has historically enjoyed broad bipartisan support. This began to change in November 2015 after one of the attackers in the terrorist attacks in Paris was erroneously identified as a Syrian refugee. Political support for the refugee program declined further after attacks in San Bernardino, California and Orlando, Florida, even though refugees played no role in those attacks.

During his campaign for the Presidency, then-candidate Donald Trump repeatedly referred to refugees as “terrorists,” and pledged to “stop the tremendous flow of Syrian refugees into the United States,” characterizing the United States refugee resettlement program as a Trojan horse bringing in terrorists disguised as refugees. He even called for a ban on the entry to the United States of all Muslim immigrants, including refugees.

By the end of his first full week in office, President Trump had taken a number of decisive steps to follow through on his controversial campaign promises on immigration.

Among other harsh enforcement measures, President Trump issued an executive order that suspended all refugee admissions to the United States for 120 days, banned Syrian refugee admissions indefinitely, and gave priority for admission to Christian refugees and other religious minorities. The order also cut by more than half—from 110,000 to 50,000—the cap on refugee admissions for 2017 set by the Obama administration.

The suspension of the refugee program in late January was, according to the executive order, intended to provide an opportunity to put in place additional security screening for refugees, a process President Trump has described as “extreme vetting” to keep out radical, Islamic terrorists. But multiple experts have confirmed that the existing process for screening refugees – which includes multiple interviews, security checks, fingerprint screens, and document review by the United Nations refugee agency, the FBI, the State Department, and the Department of Homeland Security – is more rigorous than the screening of any other immigrants to the United States.[6]

Additionally, of almost 800,000 refugees admitted to the United States since 9/11, only three have been arrested for terrorism-related activities, and none actually carried out any attack.[7]

Rather than enhancing security, the immediate result of the order has been to needlessly punish and further traumatize some of the most vulnerable people in the world who have already passed through multiple layers of security screening and been waiting for years to reunite with family in the United States.

Donald Trump has perpetuated a narrative about refugees as dangerous, unknown, and untrustworthy, and suggested that the existing system for screening refugees is grossly inadequate. If this narrative were accurate, a decision to prevent refugees from coming to the United States would seem like a reasonable response. But this portrayal of refugees and the refugee system is not at all accurate. Rather, it is a new twist on an old strategy of fear-mongering about immigrants that offers an easy scapegoat for a host of problems ranging from terrorism to overtaxed public resources. The problem is that scapegoating refugees fails to honestly assess what’s really going on or to take responsibility for offering a real solution to a dire humanitarian crisis.

Elizabeth McCormick is a law professor at the University of Tulsa College of Law, where she directs the Immigrant Rights Project.

Read more of her work and research on SSRN.

Photo Credit: This still image, taken from a video posted by the Aleppo Media Center, circulated on social media. The image shows a young boy in an ambulance after an airstrike in the northern Syrian city of Aleppo on Wednesday, August 17.