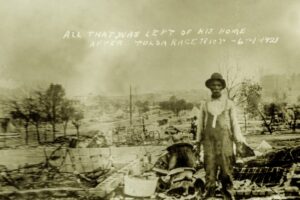

This article was originally published in June, 2020. As we approach the 102nd anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre, it is as relevant today as it was three years ago.

“Of all the preposterous assumptions of humanity over humanity, nothing exceeds most of the criticisms made on the habits of the poor by the well/housed, well-warmed, and well-fed.” —Herman Melville

In my last article from my series covering Tulsa’s history around Black Wall Street, I wrote it is unlikely the local myth about Sarah Page and Dick Rowland wasn’t much of a factor in the events that played out on the evening of May 31st and June 1st, 1921. While it is true that J.B. Stradford and A.J. Smitherman led a group to the Tulsa courthouse to ensure Rowland would not be lynched, and that a gunfight erupted between their group and a white mob (stirred up by Richard Lloyd Jones’ editorial in the Tulsa Tribune), another way to look at the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre is as two separate events.

Examining two events

The first event was the gunfight. The gunfight between the group organized to protect Rowland and the white mob began at the courthouse and moved to the Greenwood neighborhood.

The second event is the evacuation, looting, and burning of Greenwood that happened the next morning.

Spontaneous vs. Choreographed

Why separate these events?

Because the first was spontaneous—lies, that led to a scuffle in front of Tulsa’s courthouse, that led to O.B. Mann’s gun going off, escalating to a gunfight which lasted all night between the large mob of white men, and Greenwood residents, many of whom had served in WWI, less than three years previous. The white attackers did not expect that Greenwood was armed and ready to defend their neighborhood. Almost all of the gunplay ended between about 2:00 and 3:00 am. on the morning of June 1st.

And then a siren blew.

It occurred at about 5:00 am. What had been a chaotic gunfight and the setting fire of a few buildings in Greenwood’s business district earlier that night, resumed as a highly choreographed process.

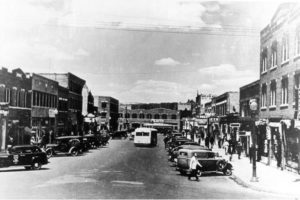

The Tulsa police, two companies of the National Guard, and an unidentified group of men in khaki uniforms systematically evacuated Greenwood residents to three holding areas (Convention Hall, which was later named Brady Theatre and today is the Tulsa Theatre, McNulty Park, a nearby baseball field, and the Tulsa Fairgrounds), looted businesses and homes, and then set fire to the entire 40-block area, including some 1,200 homes. An estimated 10,000 people were displaced. Attorney Elisha Scott released a report in October of 1921 stating that Tulsa police officer Van B. Hurley and police captain George G. Blaine had been part of a conspiracy to destroy Greenwood. The Tulsa Massacre was deliberate and planned.

We have to ask, Why?

A common answer I hear is, “White Tulsa was jealous of the wealth acquired by Greenwood.” This, too, is somewhat of a myth; a convenient explainer, but unsatisfactory.

Most of Greenwood consisted of dirt roads and humble row houses. In her autobiography, hairdresser Mable Little describes several times that Greenwood lacked a good source of water and necessary infrastructure. She complained of Greenwood’s unsanitary conditions.

While the 12-block business district along Greenwood and Lansing avenues gleamed with the wealth that J.B. Stradford, O.W. Gurley, A.J. Smitherman and their colleagues had accumulated, most of Greenwood’s businesses were run out of entrepreneurs’ homes. Most of Greenwood’s residents worked as maids, servants, barkeeps (and bootleggers) bootblacks, deliverymen, or made their living doing some form of manual labor. White Tulsa knew Black Tulsa as those who served them. What was there to be jealous of?

I submit that envy is an inadequate sin to explain the reason for the Massacre. As I’ve spent the last several years reading and researching Greenwood’s history before and after the Massacre, I’ve concluded that hatred and greed serve as more accurate sins to describe why Greenwood was destroyed. Hatred that Black business owners dared to think of themselves of having the same status as their white counterparts. Greed which fueled the plot to steal Greenwood’s land and push the Black community away from Tulsa’s downtown.

Policies of Hate

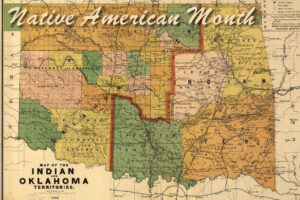

From its founding as a state, Oklahoma was all too eager to establish Jim Crow laws. Senate Bill One, Oklahoma’s first legislative act after ratifying its constitution in 1907, was to define Black and white races, and declare that “every railway company, urban or suburban car company, streetcar or interurban car or railway company…shall provide separate coaches or compartments as hereinafter provided for the accommodation of the white and negro races.”

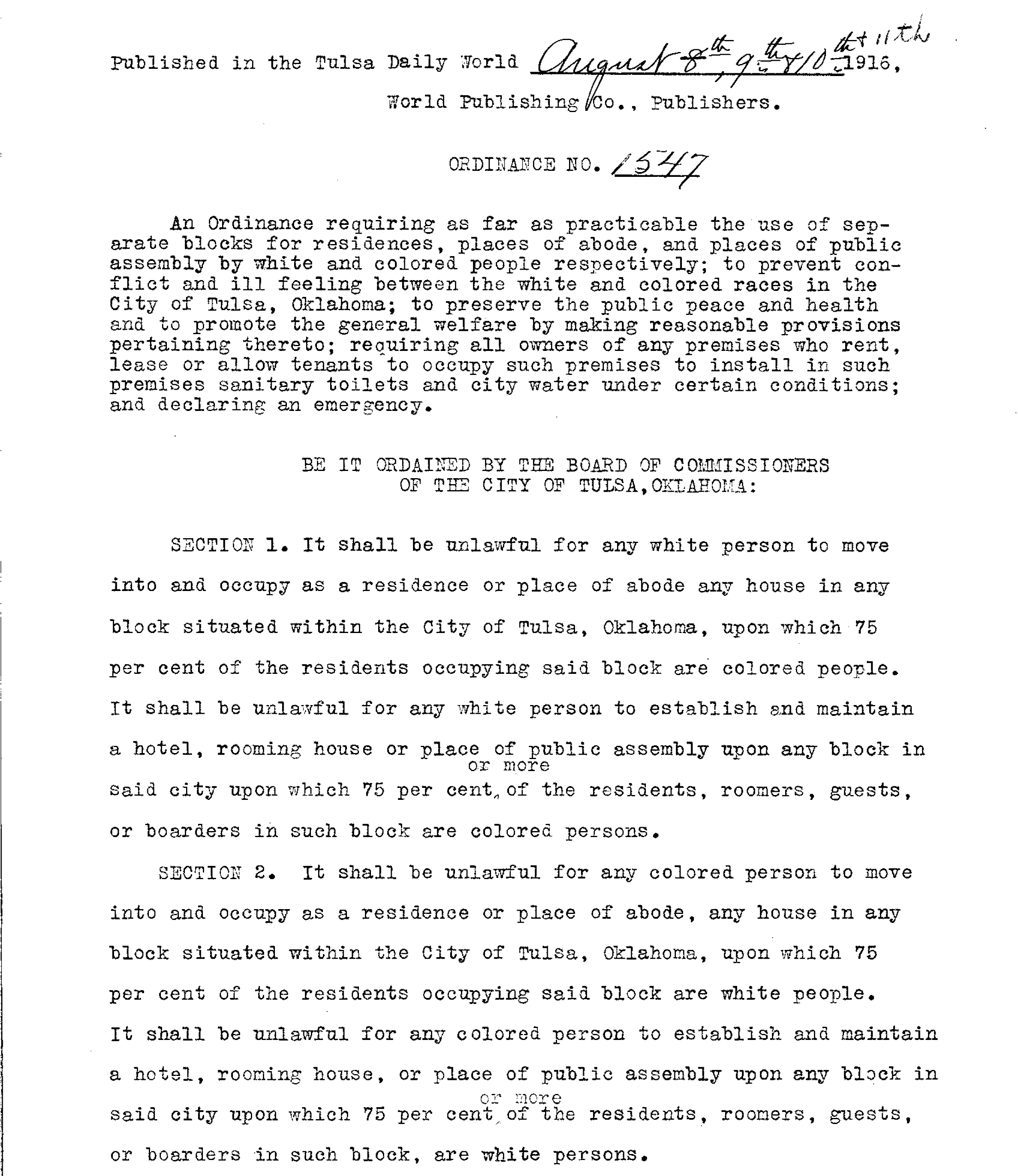

Reflect on this for a moment: Oklahoma’s first order of business was to segregate and oppress Black people. Nine years later, Tulsa’s City Commission passed an ordinance, stating, “It shall be unlawful for any colored person to move into and occupy as a residence or place of abode, any house in any block situated within the City of Tulsa, Oklahoma, upon which 75 percent of the residents occupying said block are white people.”

Protest at Dreamland

Two days later, J.B. Stradford led a protest at the Dreamland Theatre with six hundred black citizens in attendance. Stradford and his son Cornelius drafted a petition to mayor T.D. Evans, saying that the ordinance would “cast a stigma upon the colored race in the eyes of the world; and to sap the spirit of hope for justice before the law from the race itself.”

The plea fell on deaf ears; the mayor’s office upheld the ordinance.

Despite the Oklahoma Supreme Court invalidating the ordinance a year later, housing segregation remained the letter of the law in Tulsa until 1963. Housing segregation is a long and well-established racist policy, explored in Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law. These policies still have ramifications in Tulsa today.

Stradford & Smitherman

As if fighting housing discrimination weren’t enough, Stradford was also active in preventing the epidemic of lynching in Oklahoma. In 1918, he turned back a lynching mob in Bristow, Oklahoma.

Stradford and Smitherman, both attorneys, would defend victims through legal means, which sometimes included gathering a group of armed Black men to outnumber the lynch mob. Smitherman would then write about these incidents in his newspaper, as in the 1920 article in the Tulsa Star, “Near Lynch Victim Proved to be an Innocent Man.”

Law enforcement either turned a blind eye or were willing participants—the leading factors in whether someone would be lynched or not (Since Black Lives Matter protests have begun, we are seeing a nationwide resurgence in lynchings, and the same police negligence as a factor in these recent cases).

In mid-August 1920, there were two back-to-back lynchings: a Black man named Claude Chandler in Oklahoma City, and a white man, Roy Belton, lynched in Tulsa. Police Chief John Gustafson attended Belton’s lynching.

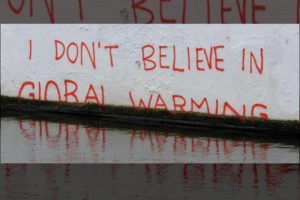

I feel it is not an exaggeration to say that Tulsa is racist by design; state-sanctioned violence and oppression of people of color lead to individuals and groups who are willing participants in racist acts.

White Supremacy vs. Black Power

We now know that Tulsa magnate Tate Brady was a Confederate sympathizer and organized KKK meetings in his mansion and a 1918 reunion of the “Sons of Confederate Veterans.” Richard Lloyd Jones, Tulsa Tribune’s owner and chief editor, was only too glad to amplify the tone of white supremacy. He never pulled punches about how he felt about Black people and the community they created, often using his newspaper to spar with the Tulsa Star.

These editorials were not just a matter of Lloyd Jones airing out his personal laundry against another journalist. He knew very well that the propaganda he published would serve to mobilize working-class Oklahomans—ravaged by the plague of 1918, still reeling from WWI, and fearful of the massive influx of Catholics and Jewish immigrants seeking jobs in the booming oil industry—to blame the Black community for all of Oklahoma’s ills.

Unmasking Parallels

There is probably no better book that describes this dynamic than Ann Patton’s Unmasked, which recounts the rise and fall of the KKK in Indiana during the 1920s. One can’t help while reading Unmasked without drawing many parallels to the recent surge in public demonstrations of white supremacy and their support in the highest levels of state and federal government.

In recent years we’ve seen the Black Lives Matter movement as a response to police use of excessive force against Black people. One hundred years ago, there were similar outspoken voices—W.E.B. DuBois, Edward P. McCabe, A.J. Smitherman, Booker T. Washington, and other intellectuals advocated to assert the rights of Black Americans. Then, as now, Black people in positions of power daring to assert their equality only added fuel to the fire of hatred.

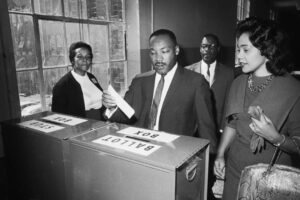

When Jim Crow laws began to change in the early 1960s, another wave of KKK activity surged in the south. And again, Black communities started to assert their rights. The first sit-in occurred in 1958 in Oklahoma City.

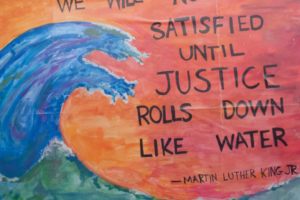

The Civil Rights movement was nothing less than a multi-year bloody battle to dismantle Jim Crow and restore some of the equality for people of color that was erased after Reconstruction.

Pendulum swings again, and again

But of course, the pendulum rapidly swung in the other direction. States no longer had Jim Crow to keep oppressing Black people, so mass incarceration, “tough on crime” legislation, and over-policing surged.

Klan rallies were frequent throughout the 1970s (it is rumored that the Klan’s regional headquarters during the ’60s and ’70s was in Glenpool), and though few and far between, continue into recent history, the last rally getting media attention occurring in 1996.

The stripping away of voting rights is another policy that has a long racist legacy—from poll taxes and literacy tests to today’s legal battles in states like Florida and Alabama (perhaps eliminating the Voting Rights Act of 1965 wasn’t such a good idea after all). As folk singer Utah Phillips reminds us, history teaches that “The past didn’t go anywhere.”

Greed for Land

We’ve covered hate. Let’s move on to greed.

The goal of the 1921 Massacre was to acquire land. Two weeks after June 1st, business developers presented a fully-developed master plan to completely redevelop the section of Greenwood that was destroyed.

The project included making Greenwood an industrial district and building a new train station along the Frisco track. The City Commission approved of this plan, passing an ordinance which made it nearly impossible for residents to rebuild their homes—re-zoning the district so that buildings had to be 2-stories tall and built with brick or stone but not wood; building materials that were far more expensive.

B.C. Franklin

The only reason that the city’s plans did not succeed in 1921 is that B.C. Franklin sued the city, and his case was heard by a panel of three County-level judges, who sided with Franklin. Residents refused to sell their land, and Greenwood was rebuilt. Loula Williams rebuilt her Dreamland Theatre 1922. By 1923, almost all of the houses that were burned were rebuilt.

By 1926 the business district was thriving again and enjoyed 40 years of peace and prosperity. Shomari Wills’ book Black Fortunes contains the words of W.E.B. DuBois, who, during a visit to Greenwood District in 1926, remarked, “Black Tulsa is a happy city. It has new clothes. It is young and gay and strong. Five little years ago, fire and blood and robbery leveled it to the ground. Scars are there, but the city is impudent and noisy. It believes in itself. Thank God for the grit of Black Tulsa.”

You can see evidence of Greenwood’s resurgence in the video footage taken by Solomon Sir Jones in the mid-late 1920s and by Reverend Harold Anderson’s Black Wall Street films shot between 1948 and 1952.

But, the battle over Greenwood’s land, unfortunately, did not end there.

Mabel Little vs. IDL

When Tulsa Model Cities was developed in the late 1960s, the city chose Greenwood as the neighborhood that would be torn down to build the IDL and Highway 244.

Mabel Little’s home and salon were destroyed by the city—again.

For losing everything she owned a second time, Little was compensated $16,000 by the City of Tulsa. She was staunchly opposed to urban renewal, observing that the building of the Inner Dispersal Loop highway system destroyed the businesses and homes in Greenwood that the community worked tirelessly to rebuild after the Massacre. She attended City Council and public town hall meetings, speaking out against what was seen by the rest of the city as positive forward progress. In the Thursday, April 9th, 1970 issue of the Tulsa Tribune, Little remarked, “You destroyed everything we had. I was here in it, and the people are suffering more now than they did then.”

As with race massacres, redlining, voter disenfranchisement, and the surge of white supremacist organizations, the federal highway program was a national catastrophe, devastating to minority neighborhoods.

Land Ownership, Wealth and Tulsa’s greater sin

Yet another blow came to Greenwood in the late 1980s. The city purchased everything that was not bulldozed to build the highway to create the University Center of Tulsa (UCAT), and today the majority of what was once Greenwood’s residential area is OSU-Tulsa andLangston University-Tulsa.

Today, what was unfinished business in 1921 is getting completed with gentrification, and purchase of land in North Tulsa by the Tulsa Development Authority, known as TDA—the same organization that stole Greenwood land to build the highway.

It is no secret to anyone who has even a passing knowledge of economic policy that land ownership equates to the building of wealth in communities. Therefore it is perhaps the greater sin is that Greenwood’s land—and therefore the opportunity for the building of generational wealth for North Tulsans—was stripped away in 1921, in 1971, and again in 1991.

On June 4th, 1921, Lloyd Jones wrote, “the old ‘N—ertown’ must never be allowed in Tulsa again.” While the Chamber of Commerce at the time had set up a committee for reparations for Greenwood, the mayor and other city leaders insisted that the black community be moved further north, away from downtown and away from Tulsa. The latter faction prevailed, the fund to help Greenwood was shut down, and the City put the blame on the neighborhood’s destruction on the Black residents of Greenwood.

A similar battle is happening today. While residents and business owners in North Tulsa are attacked for trying to protect their people and their land, it is being bought from them wholesale, behind closed doors, aided by Tulsa’s government agencies. Simply put by Black Wall Street Times founder Nehemiah Frank, “Gentrification might do what violence couldn’t.”

Carlos Moreno is a member of All Souls and serves on the board of directors, as well as TulsaRISE and as part of the leadership for All Souls Shādz & DIVE groups.

He was selected by national urban-affairs magazine NextCity as part of its 2014 Vanguard Class. In 2015, he was certified by IDEO and +Acumen, in the practice of Human-Centered Design. Carlos earned a Bachelor of Arts in Administrative Leadership in 2017 and a Master of Public Administration (MPA) degree with a focus on civic technology in 2020 from the University of Oklahoma. Carlos is the author of two books: The Victory of Greenwood (published by Jenkin Lloyd Jones Press) and A Kids Book about the Tulsa Race Massacre.

Cover photo: John Wesley Williams and wife, Loula Cotten Williams, and their son, William Danforth Williams, sitting in their 1911 Chalmers touring car. The Williams family owned the Dreamland Theatre, which opened in 1914 at 129 North Greenwood Avenue, and was destroyed in the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. Photo courtesy of the Tulsa Historical Society and Museum.