My delve into Hauerwas’ Christian criticism of liberal democracy coincided very well with one of the most depressing electoral results, and everything since then, that I can imagine. What better time to contemplate the futility and utilitarianism of democracy that at the time when America is electing a woefully under-prepared, proto-fascist to be the most powerful man on the planet?

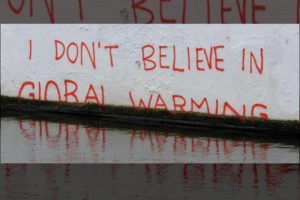

I actually think the election of Trump reinforced the message I was getting from Hauerwas; namely, that democracy is not inherently moral. This isn’t to say that it is immoral. Rather, democracy is a morally neutral system, a tool we humans use to order our governance of our selves. Self determination, self government: those are moral ideals. Democracy, as the tool used to achieve them, is not.

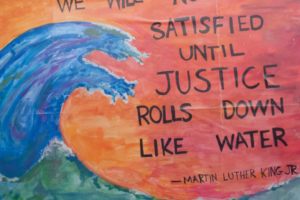

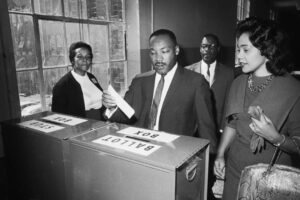

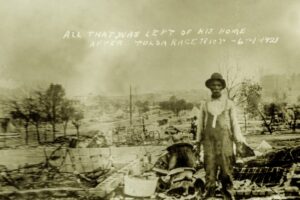

One of the ideas that so many people struggle with (and I admit I did for a long time) is that we expect democracy to produce the “right” answer. We expect, no matter our ideology or political party, that in the medium to long-term, regardless of the outcome of various immediate elections, that the democratic process will conform itself to Dr. King’s moral arc of justice. And sometimes it certainly feels that way; for me, 2008 was one of those times. It was hard for so many people to not perceive the election of Barack Obama as not just a good thing, but the morally inevitable thing that democracy promises us.

But this just simply isn’t the case. In and of itself, democracy is no more moral that any form we use to govern ourselves. Now, democracy comports itself better to the ideal of self-determination better than republicanism or oligarchy or even Plato’s rule of the elite does. But, in the end, democracy facilitates the ability of the mass of people to make a certain choice, regardless of the moral weight of that choice. Another way to say this is, we get what we vote for. And sometimes, that is a Barack Obama, or an Abraham Lincoln, or a Solon, or a Nelson Mandela. But, sometimes, it’s a Donald Trump. In democracy, the right choice isn’t always the moral choice. The right choice is just whatever we decide it is. Democracy is only as moral as we are as a people.

The equation of democracy with morality is one of the original sins of American political engagement. Because we have allowed our democratic experiment to so often be equated with the Kingdom of God – because we like to entertain the notion that American democracy is a divinely ordained institution – we accept the logical conclusion that American democracy must be a force for good in the world always. It’s not.

Democracy is another tool for ordering this world. And it is a particularly good tool, compared to so many of the others we humans have tried. Churchill’s rumination on the merits of democracy is quoted often today, but rarely taken to it’s logical conclusion. Those of us who identify ourselves as Christians have an obligation to not identify our faith with that of something as human – and thus as fallible – as democracy. Our hope is not found in such things. Democracy can be useful, and can do good things. But the redemption of our world – the coming of the Kingdom – is found in ideals beyond simply the logistics of choosing new leaders. Our hope is found in the radical love that is our God, and that was lived by the man whose example we follow.

That’s an important reminder in a world that just elected Donald Trump. His elevation to the White House is disheartening, frightening, and dangerous. We have a lot of work in front of us, in terms of standing with and for those who need our love and solidarity today. But, frankly, that would have been true, albeit on a less severe scale, even with the election of Hillary Clinton, or Bernie Sanders. This is what we would do well to remember in the heat of the next electoral cycle: the election of a candidate we favor doesn’t mean our work is needed less. On the contrary: the election of Hillary Clinton would have made our work just as important, because rather than working to hold ground (as we are going to be doing for the next four years), we would have been compelled to move justice forward – and that is just as vital and hard of work as we are facing now.

The promise of democracy is not the same as the promise of love. We shouldn’t forget that, and we should never equate the two. The right answer will never be the one supplied by democratic promises; the right answer is the hoped-for Kingdom, the one we have the power to bring here, not at the ballot box, but in loving those we meet everyday.

Reposted with permission from Justin DaMetz, Progressive Christianity, Theology, Social Justice