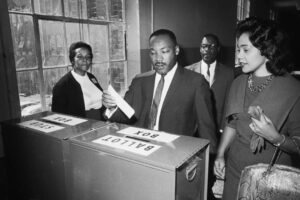

In 2009, the Unitarian Universalist Association chose a clarion title for its social-justice advocacy campaign: “Standing on the Side of Love.” Today, the campaign continues to serve as an umbrella for work on behalf of members of the LGBT community, members of racial minority groups, Muslims and others who are targets of discrimination and hateful acts.

After an election that has revealed an America more deeply and bitterly divided than many of us had realized, it is a good moment for us to step back and examine the way we think and talk about love, sides and the imperatives of social justice.

Standing on the Side of Love grew out of the UUA’s solidarity with the marriage equality movement, an origin that puts the campaign’s title in specific context. The love was understood to be that shared by same-sex couples and equally worthy of the right of marriage. Today, in the context of a diversified social justice campaign, the title is susceptible to a broader interpretation. Taking the words at face value, we are likely to see ourselves as representing the side of love in general.

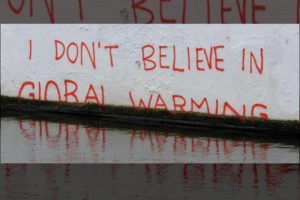

We need to be careful here. To think of love this way is to place it in an adversarial frame and to proclaim ourselves in the right. This move is dangerous in two respects: First, it entails the dehumanizing idea of a loveless other, and second, it insinuates a seductive hero narrative. When we “stand on the side of love,” we too often reserve a little part of ourselves that can run over to the next hill and admire the glorious scene of set jaws, billowing flags and cascading sunbeams. If we’re not careful, our work can become more focused on maintaining this heroic self-image than on making the specific difference we need to make.

The first version of this essay – the one written before the election – went no further than this. I argued that “standing on the side” invited antagonism and vanity that were at odds with the deep, transcendent nature of true love. “Love is not a side,” I had written, “It’s a way.” I still believe this is right.

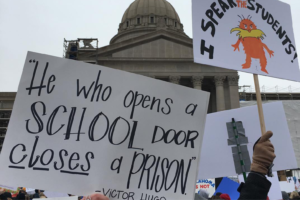

But now, I think we need to draw a clear distinction between love and justice. The first transcends antagonism at the individual level. The second requires it at the social level. As far as the machinery of the American social system is concerned, there are, indeed, sides. And now more than ever, there are lines that must be defended – fiercely and without apology. This is best framed as a matter of justice, not of love.

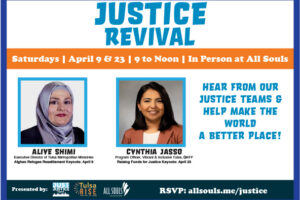

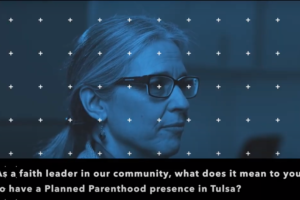

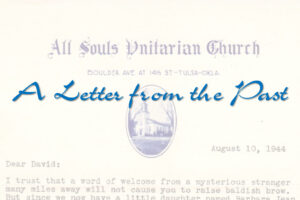

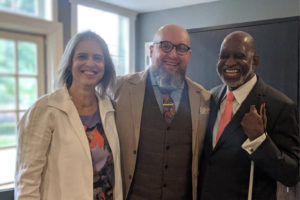

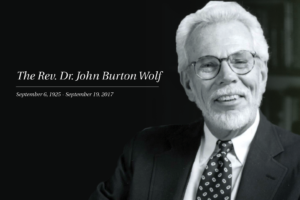

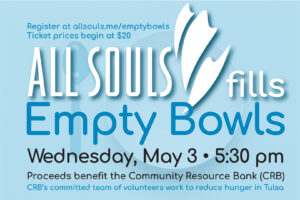

Within the All Souls congregation, there will be significant though not complete agreement about the import of Donald Trump’s election to the presidency and a one-party government. There also will be significant though not complete agreement about how we should enact the UU tradition’s express commitments to individual dignity, democratic process and ecological stewardship, among other points of conscience. Under ministerial leadership, the prevailing judgement of our congregation will guide our social justice work. Where there are disagreements, the work of covenantal love will begin as we recognize and respect the inherent flame of humanity/divinity within each of us that transcends difference.

Words do matter, and for the sake of clarity, I recommend that the UUA drop the legacy title and refer to its social justice initiatives simply in that way: “Social Justice Initiatives.” Though generic, this title does not confuse love and justice, and it removes any romantic ground-standing imagery to keep the focus where it belongs. It’s not a dressed-up slogan, but a businesslike title for a moment that calls us to be fully and vigilantly about our business.