All Souls member, Rev. Doug Inhofe talks about taking chances and living an authentic life in the Humanist Hour on July 30, 2017.

When I was in my fifties, and wondering (still!) what life was all about, especially an authentic life. I talked to a lot of people to see what they thought. Looking for some real-life data, I spoke to Brent Smith, then the senior minister at All Souls. One of the things he said stuck with me, and it was this: ministry is perhaps the last authentic profession . . . possibly one of the few remaining authentic ways of making a living.

Having taken up Brent’s encouragement, I headed off to divinity school where I continued to work on what he had said and what living an authentic life really meant for me.

Ultimately, at the end of three years, I concluded:

To live an authentic life, regardless of what you do in it, means to do the right things for the right reasons.

It was just that simple.

Now, I can parse Brent’s prescription into four parts:

- First, we are free to craft our lives, within the circumstances in which we are immersed;

- Second, in making our choices about our lives, we should take the position of someone down on the field, and not be a spectator;

- Third, while we’re down on that field, we should recognize that choice, commitment, responsibility, and risk are inescapable;

- Fourth, we should then live out our choices authentically.

Just four things to do here, and then I would be all set to live my authentic life! At one level it sounded direct, and thus appealing.

All I ever needed to do was to:

- Take into consideration all the possible outcomes, and all the values bearing on them

- decide to decide

- to act on my decision.

- to be satisfied, if not happy, about it.

Or, was this just a way of reducing to words a truly complex mental operation—one so complex that its reduction into four discrete pieces—and then into words—was almost laughable?

But there at the end was this phrase “authentic life”—and I thought that was what I was trying to define in the first place! What was to be done?

Well, there’s poetry.

The four-part reduction is just a start, and it’s a good one, but it takes some fleshing out. When I delivered this talk, Living an Authentic Life, in the Humanist Hour, I also provided the reading, and excerpt from Adrienne Rich’s Transcendental Etude.

The four-part idea—including, implicitly, the necessity to choose, and the idea that to delegate your choice or not to choose at all is itself a choice, but one constituting and act in bad faith to yourself—has some currency.

Having crystallized out of a literary tradition beginning with Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, in the middle of the nineteenth century, running through Camus’s The Stranger and Sartre’s Nausea in the middle of the twentieth. Camus, for his part, said that there were four principles to happiness: love someone, live in the open, forsake ambition, and do something creative.

But of course to use these prescriptions, one’s frame of mind must be of a certain kind, and so it probably proves too much to say, “Here, do these things, you’ll feel good about it.”

We need to look into how we actually experience the world—what’s out there that can help, inside us, to live our lives? Rainer Maria Rilke, an Austrian and Swiss poet, tried to answer this question in his poem, On Art—this is, he says, how our free will can really take off:

Not any self-control or self-limitation

for the sake of specific ends,

but rather a carefree letting go of oneself:

not caution, but rather a wise blindness;

not working to acquire silent,

slowly increasing possessions, but rather

a continuous squandering of all perishable values.

[Rainer Maria Rilke Austria, 1875-1926), “Über Kunst”; shown at p. 70 of Daniel Dennett’s Elbow Room]

Rilke has taken our four-part idea and tucked it in a bit. Now it’s three. But, what is a carefree letting go, what is a wise blindness, what values are perishable? Again, everything must be placed in context.

If I told you to “be cool,” you might ask, what does “cool” mean? Once it meant dignity and self-control in the face of oppression, but now it might mean a way of being instinctual and primitive, or artful and sophisticated.

Only our experience with how things actually work—which choices have been good ones, which bad, and what were their effects—can create and inform the process inside us for making authentic choices.

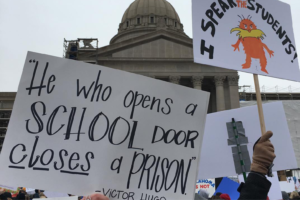

Making choices is something we need to practice, and thus a value that transcends our four-part idea would be one that cultivated the process of good decision making. This meta-value tells us to give children and young adults chances to make their own decisions, so they can have their very own authentic history, of their very own authentic choices.

To put it another way, if all twenty-year-olds conducted their lives as seventy-year-olds would conduct them, then nothing new would ever happen in the world.

No one would ever get far enough from the shore to discover new lands.

It’s not what our children are doing that matters so much as how they’re doing it.

The freedom to be free gives people a palpable sense of imminent good fortune that, in itself, helps them to lead lives of dedication and conviction, with verve, flair, and style.

And so it is of greater importance for us to think for ourselves than it is to know, precisely, what to think. Now of course there is a huge middle-ground in there, but in the beginning it’s often a very dialectical world for kids, all yin or all yang, not much down the center.

The freedom to be expressive, without fear of being wrong, is like the computer’s operating system. It comes first. Let your expressive self run.

The content, your editing self, will ultimately be shaped by the freedom to choose the experience that follows. The essential ingredient of one’s first solo is confidence. If there’s a content problem, well, that’s what the rest of our lives are for.

Being in thrall to freedom is, of course, not enough. At some point we must be filled with responsibility and truth.

Remember, responsibility and risk are inescapable, so, as we grow our sense of freedom evolves, we take risks, we shoulder responsibility, and we begin to have our freedom, instead of its having us. When we were young, and we had chores, then our responsibilities had us. Now we have them.

Now I’m seventy something, and I’ve got some experience . . . and some content . . . and have made some choices. I’ve been doing my best to be authentic! And then I read in a book, Younger Next Year, that at my age I should just say “yes” whenever there’s a chance to do something, or go somewhere, or participate—especially in something new!

I take this to mean that it’s important to still be down on the field, as a participant. But, I wonder if the point of being a player is deeper than just being involved. I think the book has instructed me to choose, and to take a chance despite my uncertainty.

In other words, what’s good for children is good for me: The freedom to be free would give me a palpable sense of imminent good fortune that might help me to a life of dedication and conviction, with verve, flair, and style… an authentic life, that is.

Now, a short story on this taking a chance idea.

Recently, I bought a lottery ticket, the kind that would pay a winner millions of dollars. The rationalist side of me said it was literally a waste of time, that the odds were so staggering. I even wondered about the ethics of lotteries–played by many people who had little money to spare, and designed to take that money in exchange . . . for what I saw as a hollow hope!

So why’d I buy? Well, when I did it, I said it was to see what the ticket looked like, to see how the numbers were selected, to learn how and when I could follow the drawing. And strangely, after I had the ticket, I was careful to put it in a pocket where I knew it wouldn’t fall out, and when I got home, I put it in a place where I knew it would be safe. It had become an icon of something.

I was amazed that I could feel a sense of possibility. In my world, a money doesn’t come from chance, but from diligence. I don’t quibble with the value of diligence, but I did see the attraction. There’s a song by Dire Straits called “Money for Nothing,” where, in the song, the lead singer is a man who struggles all day to deliver refrigerators and custom kitchens and color TVs and who laments the life of a rock star, who might suffer . . . a blister on his thumb. There are a lot of people for whom “money for nothing” is the only way to get there from here. Their hope is in the unpredictable world of random number generators. The ticket for them represents faith, or hope, and thus the lottery itself is like secular salvation, at the least. Or, at worst, it’s a path to addiction.

It was this feeling that explains the popularity of lotteries, it explains why people buy, even though the odds against winning anything are ridiculously long.

Consider this. Being responsible for our choices is an invitation to regret ones already made—if you look inside yourself for a sense of order in the world, then you might also be inclined to look inside when things go wrong. Sure, regret is a great teacher, one of the best, but it might also be the beginning of original self-blame.

One way out of this box–of being both free and yet responsible–is to subscribe to a certain kind of scientific materialism, to return, in a way, to an earlier world when fate and destiny held sway. This new form of determinism says to us, “Look, don’t feel so bad, in many ways science tells us that we are trapped by the physics of our existence. You are not as independent as you think. You don’t have as much ‘choice’ leeway as you think. It’s really a much more deterministic universe than you thought–perhaps, when you made that choice (the one you now regret), you really could not have done otherwise, no matter what you thought at the time.” On E. O. Wilson, his Consilience (New York: Vintage Books 1999, at p. 130), and his point there:

“In the naturalistic view, free will in [the] deeper sense is [nothing more, or less, than] the outcome of competition among the scenarios that compose the conscious mind.”

So, this brings me full circle, back to the new devotional practice of buying that lottery ticket. Back, perhaps, to a world of quantum randomness where nothing is certain, where everything is probabilistic. Roger Penrose, an Oxford mathematician and one of Stephen Hawking’s cohorts, has actually argued in his 1980s book, The Emperor’s New Mind, that sub-atomic randomness is the very source of our free will. Maybe, despite Einstein’s take on it, God really does play dice!

But here’s the point.

Chance, you see, sets you free from a world of systematic control.

Now, to be sure, chance is not a thorough-going philosophy, it’s not one for all of one’s life, but to many it has the appeal of an elixir. Chance creates an ever-new world for adults, young and old, a world where everything is not already fixed.

Turning one’s back on tradition–taking a chance–is a way of stepping outside of today’s contemporary world, a way of slipping through a portal of possibility and escaping a too-rationalistic, a too-utilitarian, a too-controlled world. By giving up the drive for a perfect mastery of the future, taking a chance recognizes that the pursuit of happiness invariably defies our attempts to organize it.

The idea is set forth forcibly by Jackson Lears in his article, Gambling for Grace. Like artists, he says, people who take a chance, who cut against the grain, “implicitly acknowledge that Fortune is best courted obliquely rather than confronted directly, and that the willingness to experience chance creates the possibility of [an enlightening and an enlightened life].” William James once said something similar, telling us that chance was a kind of gift, “something on which we have no claim,” and that it stood squarely against the Victorian ideal of a systematically controlled life, that it betokened the flair required to make our selves soar.

If I had to guess, I would say that many Unitarians would be sympathetic to William James’ insights–ones subsumed, strangely enough, in a philosophy generally described as pragmatic. With our status as free agents, by being open to the possibilities that we create with our choices, we can confront fortune obliquely, we can experience the possibility of great beauty, and we can, at the same time, keep ourselves open to the realization of our dreams to live an authentic life.

This openness can be our motive force. It can be the fuel for our lives, springing out of our sense of personal freedom, out of our now-evolving sense of responsibility, and, in itself, it can give us a sense of triumph that will help us weather the difficulties that are almost certainly ahead.

We might never be rich, but we will never be weary.

In sum, saying “yes” beats saying “no” . . . all things considered. And one of those things can be this:

Take a chance.

Find more inspiration from poetry on Beyondbelief.online. All Souls member Mia Wright shares her words and prose about universes and melodies during Sunday services in January.