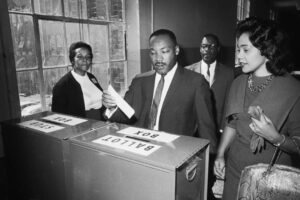

It seems like months have passed, but the video of Amy Cooper calling the police and lying about being attacked by a Black man (comic book writer and birdwatcher Christian Cooper) occurred on May 25th, just a few short weeks ago. The tweet went viral immediately, retweeted by Booker T. Washington High School grad, former Oklahoma City Thunder player, and political activist Etan Thomas, as well as hundreds of Black leaders, social justice activists, journalists, and the birdwatching community.

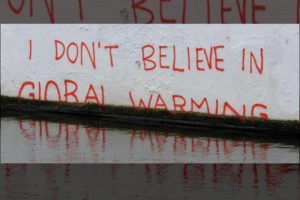

Weaponizing the police is almost commonplace on social media.

In May of 2018, Jennifer Schulte called the Oakland police to complain that Black men were barbecuing in a public park. In the same month, an elderly white woman in Palo Alto, CA, called the police, who harassed filmmaker Kelly Fyffe-Marshall and her friends as she was leaving an Airbnb. Employees at a Nordstrom Rack in Brentwood, Missouri, called the police, falsely claiming that three Black teenagers were shoplifting. A few days later, a white Yale University student called the police, who interrogated Lolade Siyonbola for taking a nap in a dorm common area. The previous month, two Black men in Philadelphia were arrested for meeting in Starbucks. One need not scroll very far down their Twitter or Facebook feed to see yet another one of these types of incidences appear; across the country, these videos are appearing seemingly every week.

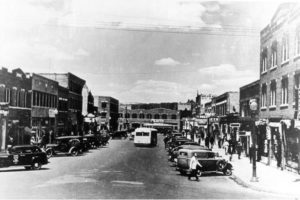

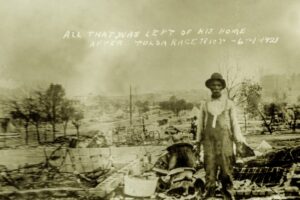

Memorial weekend — 99 years ago

Media outlets began connecting Amy Cooper’s phone call to another Memorial Day incident— 99 years ago. On May 30th, 1921, an elevator encounter between Dick Rowland and Sarah Page is said to have set the wheels in motion for Tulsa’s Race Massacre. CNN reporting for ABC Chicago quoted Greenwood Cultural Center director Michelle Brown, who said, “Page initially claimed that she was assaulted.” In another interview for CBS Sunday Morning, Brown was quoted saying, “a man working in the building came running to see what had happened, and claimed that Sarah Page had been assaulted.” Most famously, in a Huffington Post article titled, Amy Brown Knew Exactly What She Was Doing journalist Zeba Blay wrote, “Sarah Page claimed that Black shoe shiner Dick Rowland assaulted her.”

But a Black Wall St. Times editorial written by local J. Kavin Ross tells the story most accurately according to what we know today: “Known by his friends as Diamond Dick, he was seen by a clerk fleeing from the elevator. He continued to run towards Greenwood. The internet was yet to be invented, but news spread throughout the community.”

Historically inaccurate to equate Amy Cooper and Sarah Page

While it is utterly disgusting for white people to use 911 and the police department as their personal racist customer service hotline—to say nothing of the fact that these phone calls put Black people at risk of significant physical danger—it would be historically inaccurate to equate Amy Cooper and Sarah Page.

We know from recent research that Sarah Page was asked to testify against Dick Rowland and refused. She and Rowland were in a romantic relationship—interviews from the 1920s and later accounts of the events leading up to the Massacre that substantiate that claim. Page and Rowland’s elevator encounter occurred on May 30th.

Tulsa Police officers Henry C. Peck and Henry Carmichael—one Black, one white—found and arrested Rowland on the morning of the 31st. Had police chief Gustafson taken the elevator incident seriously, it’s not likely that he would have waited the next day to dispatch police officers to Greenwood to find Rowland and arrest him.

Victory of Greenwood: Telling the stories of the Black Wall Street era

I wrote for the Victory of Greenwood: “On the morning of May 31st, 1921, Dick Rowland was found and arrested for the alleged assault of Sarah Page. During the evening, he was held in the jail at the top floor of the Tulsa County Courthouse when the police brought Page in to testify. There is no written record of her testimony, but according to Riot and Remembrance: The Tulsa Race War and Its Legacy by Boston journalist James S. Hirsch, Page said that the incident in the elevator was a misunderstanding and she did not want to press charges. Rowland was scheduled to be discharged from the jail by a judge the next morning. Had this been an ordinary case, the matter would have ended right then and there, but what followed was anything but ordinary.”

The only reason he wasn’t released the same day is that by late in the evening after both the Sheriff and the Chief of Police failed to charge Rowland with something—anything—they would have needed a judge’s signature to release him from the holding cells at the top floor of the courthouse. Sheriff McCullough didn’t want to bother the judge (it was a holiday weekend and, saying that he was not feeling well, the judge had gone home early to rest). So he decided that Rowland’s release could wait till the next morning.

Fake News—99 years ago

Meanwhile, a story in the May 31st morning edition of the Tulsa Tribune with the headline, Nab Negro for Attacking Girl In an Elevator circulated. Tribune owner and editor Richard Lloyd-Jones wrote that Rowland was “charged with attempting to assault the 17-year-old white elevator girl in the Drexel building…” Both facts in this sentence are a lie.

Police did not charge Rowland, nor did Rowland attempt to assault (a word used in those days to mean rape) Page. But journalistic integrity was of no concern to Lloyd-Jones when it came to Greenwood or any of its residents.

By this time, the Tribune was well-known for its inflammatory remarks against Greenwood: Never referring to the neighborhood by its proper name, he called the area “Little Africa” or “N—er Town.” The Tribune was also famous for its regular sparring in its pages with one of Greenwood’s newspapers, the Tulsa Star.

Missing Microfilm & No Charges

Historians claim that an even more incendiary article appeared in the evening edition of the Tulsa Tribune. However, no copies of that issue have been found, and pages are missing from the microfilm of this issue. Some have even theorized that the famous “missing editorial” from the Tulsa Tribune‘s evening edition never existed. Historically, this makes sense; by this point it was clear that there were no charges to be brought against Rowland.

The unfortunate truth is that we may never know what happened between the couple, or what Lloyd-Jones wrote about them (if anything) on the evening of May 31st.

I do not say this to let Richard Lloyd-Jones off the hook. But the notion that the Tribune’s editorial about one woman being attacked hit such a nerve with the white Tulsa community as to cause the level of destruction that the Massacre did, is somewhat of an open question.

Reports find the Massacre was planned

Elisha Scott, an attorney from Topeka, Kansas investigated the massacre and two newspaper articles from October, 1921—one in the Phoenix Tribune and one in the Dallas Express—reported that Scott had received a confession from Tulsa police officer Van B. Hurley. Hurley claimed the Massacre was planned, and named police captain George G. Blaine as one of the conspirators.

If his findings are correct (Walter F. White, an investigator for the NAACP came to similar conclusions in his June 1921 report, The Eruption of Tulsa. Maurice Willows, in charge of the Red Cross’ relief efforts for Greenwood wrote a report in December of 1921, agreeing that the destruction of the neighborhood was premeditated), the Massacre had almost nothing to do with either Page or Rowland.

The more I read, the more I keep putting more of the pieces together, the more I conclude that the role that Page and Rowland played in the events that occurred was a minor one at best.

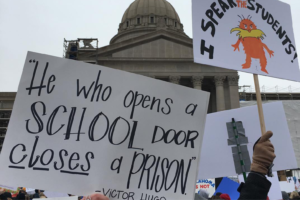

Those who planned the Massacre wanted Greenwood’s land. And what kicked off the fighting and destruction had a lot more to do with police negligence and less to do with the allegations against Rowland (one can’t say he was falsely accused if he was never accused of anything.)

A counter-argument could be made that he was tried in the media, but the Tribune in 1921 was the equivalent of InfoWars; they published a racist screed in almost every issue—why would this small editorial make such a difference? Why would the arrest of one Black man result in the burning of 40 blocks? Even if it did, why didn’t more of downtown get damaged? If the Massacre was such, “chaos” why only those 40 blocks?

The news of the time tells the story story

Greenwood was going to get burned down whether Rowland had gone to the Drexel building or not. Pulling back and looking at the bigger picture, I think that the story of Page and Rowland is a convenient narrative that hides much bigger, underlying conditions allowed for the Massacre to happen. If you look at what was being talked about back then, in court testimony and news articles after the Massacre, it was not Page and Rowland; it was the power struggles, it was housing and transportation segregation, systemic racism, lynchings, and police corruption & negligence.

Within two weeks, the City Commission had unveiled a master plan for kicking Greenwood residents out of their neighborhood and building an industrial district and train station. Ads soon appeared in the Tulsa World, urging Greenwood residents to sell their land to white developers.

That plan failed because Greenwood refused to sell their land and the city was sued for its participation in the attempted land grab. The City Commission passed a resolution that had the goal of preventing residents from rebuilding their homes. B.C. Franklin sued the Commission, the Mayor, the Chief of Police and the building inspector for the city over this ordinance and a panel of three Tulsa County judges agreed with Franklin that Greenwood residents were unlawfully being forced off their land.

Sifting through the Ashes, before and after

We have this citywide narrative that begins with Page and Rowland in an elevator and ends with Greenwood being destroyed.

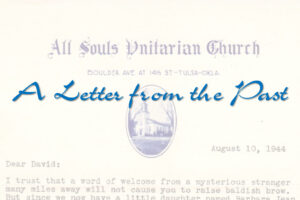

We’ve never sifted through the ashes to find out what happened before and after the Massacre. Digging up primary sources and telling Greenwood’s story more fully is the goal of the Victory of Greenwood project. It consists of a series of articles that will be compiled into a book, published by All Souls Church’s Jenkin Lloyd-Jones Press in May 2021.

As we do reflect on recent events and tie them to our nation’s history, we must try to understand historical context and its complexity as much as possible, especially our own city’s cultural narratives.

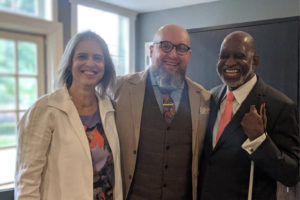

Carlos Moreno is a member of All Souls and our Criminal Justice Outreach team. He recently launched the site, The Victory of Greenwood, telling the stories of Greenwood from perspectives of the heroes and entrepreneurs who built Greenwood, and rebuilt the community after its destruction. Carlos is an advocate for criminal justice reform in Oklahoma. Read more from him about CJO’s work in Poetic Justice and Prison and The Biology of Toxic Stress on beyondbelief.online.

The All Souls Criminal Justice Outreach team CJO seeks to care for those impacted by incarceration, to educate the community about criminal justice issues, and cultivate equitable reforms in Oklahoma’s Criminal Justice System. Please reach out via email or join our Facebook group if you’d like to join CJO or have questions.

7 Comments

Carlos,

What an excellent article. I absolutely agree with your comments. I remember Eddie Faye Gates saying that the two were lovers in the 1990’s as I would follow her on tours. I absolutely misspoke by saying that Sarah Page ever accused Dick Rowland. Thank you for checking me!

Carlos, thank you for the fascinating article peeling back some layers on the narrative surrounding the race massacre. This is important work for us to truly and fully grapple with our history and the unhealed wounds that remain in our community to this day.

[…] […]

[…] the last two articles of this series, I have discussed some myths around the Tulsa Race Massacre. For a moment, […]

[…] and rebuilt the community after its destruction. Read his take on weaponizing the police in Sarah Page was No Amy Cooper and Police Brutality is Nothing […]

I found Carlos article about the subtext behind the 1921 Tulsa riot fascinating and inspiring. I have read a lot about the infamous incident in Greenwood Oklahoma and, this article serves in my opinion as a capstone. I also, thoroughly enjoyed the highlighted history of some its noted residents like B.C Franklin and Bass Reeves. Overall, Mr. Moreno’s work reflects the highest journalistic integrity I’ve seen and he is to commended for his work and continued efforts.

Mostly good article and someone else may have already chimed in, but there’s some ongoing false myths presented as fact here / written in a way to establish the framework. Hopefully good writers can avoid doing this especially when the subject is so important.