By Robin Ballenger –

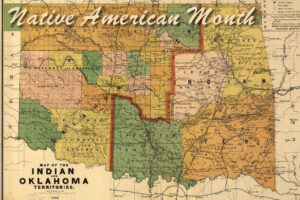

I know we Unitarians pride ourselves on our analytical thinking habits, but I will say right up front that my spiritual practices are not rational. Really, they are not even practices. They arise out of two cherished long-ago places, and are a mixture of my Cherokee grandmother and my camping days in Minnesota. They make no sense even to me, and I share them with some discomfort.

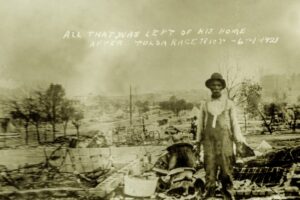

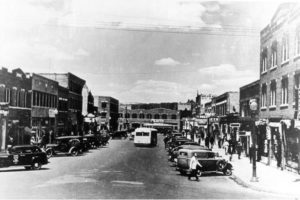

My Dad’s mom was a full-blood Cherokee, living in two worlds. She married my Anglo grandfather and moved from my family’s original land allotment in White Oak, Oklahoma to Tulsa. Always torn between two cultures, she lived the life of a society matron in Tulsa, and went back to White Oak for Stomp dances, ceremonies and the family that did not trust her new white ways. I remember driving with her from Tulsa for the Green Corn dance, watching her become more Native with each mile. Her hair came down, she put on her moccasins, she became freer. From her I learned as a very young child that I should hide that Native heritage the way she hid her medicinal plant garden behind the garage in Tulsa.

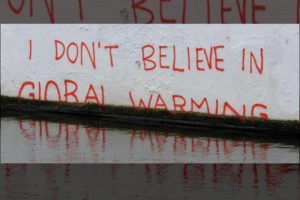

I still grow a few of her plants in my backyard beds, but I cannot remember how to properly dry them and make them into healing agents. I still go to Stomp for Green Corn in the summer, and feel the generations moving in my legs. I remember the Cherokee value of Balance, that a life must be balanced with its surroundings and that a life out of balance brings destruction and heartache. I feel closest to that balance when I am walking as the day moves to evening. That is a crucial spiritual practice for me.

My second spiritual practice, and I use the term loosely, is my way of measuring the worth of my actions….how I evaluate how I am doing as I move through the world.

I have never understood religion. I have felt awe, and I have experienced Grace, and I try to live a good life, but religion eludes me. Even as a child, when my friends were taking first communion, learning what Presbyterians or Methodists or Jews believe, or wearing crosses around their necks, I was baffled. I tried so hard to “get it.” I was troubled by my failure to grasp religion, because I wanted a code to live by, a set of beliefs to guide my life.

I found my set of beliefs as a summer camper in the Minnesota Northwoods. One rainy afternoon, I stood in the lodge by the fireplace. There, hanging crooked on the wall, was a framed copy of The Campers’ Code. The frame was dusty and battered, and it looked to be generations old. This was certainly not a promising place to “find religion.” But as I idly started to read through the cracked glass, I began to understand that here might be my own code, one that could guide me into my future. I remember still the peaceful feeling that came over me.

I am now 70, many decades past that rainy afternoon, and to this day I carry a copy of The Camper’s Code in my wallet. At crucial crossroads I take it out and reread it to show me the way. Many would say the Campers’ Code lacks the sophistication to be of use in today’s wild-paced world. I would disagree. It is all there in the Campers’ Code, everything I have needed.

These two taproots, my Native heritage and the code of conduct I learned long ago at camp, have given me a strange bedrock upon which to build a life. But there are many kinds of lives, and I am grateful that I can sit here and write this, and know that at All Souls, mine might not be the strangest.